Glacier’s Glaciers

A somewhat whimsical guide to the glaciers of Glacier National Park

As part of my training to be a hiking guide in Glacier National Park, I was required to give a short presentation on a subject relating to what makes the park unique, its history, or a scientific subject relevant to the park. I was assigned the topic of Glacier’s Glaciers and enjoyed working on my presentation so much that I wanted to share it here for anyone else who might be interested! It’s also one of the most frequent subject matters I get asked about as a guide.

So without further ado, ladies and gentlemen, may I present to you… Glacier’s Glaciers.

What is a glacier?

The true definition of a glacier is a mass of ice so heavy that it flows under its own weight. Imagine pressing down on an ice cube on a flat table. As you added more and more weight to the ice, the pressure would eventually become so intense that the ice would slide out from under your hand, leaving a trail of water in its wake. A common threshold for determining if an ice mass might be big enough to flow under its own weight is if the ice covers an area of .1 km squared or about 25 acres. If 25 acres is a measurement that doesn’t mean much to you (hello, fellow non-homeowners!), that is about 19 football fields, 6 Walmart supercenters, or 4050 parking spots. Ice masses of less than 25 acres can flow under their own weight, and larger ones sometimes do not. Still, this statistic is often used as a touchpoint and determiner when discussing the glaciers in the park.

How many glaciers are in the park?

According to the National Park Service, at the end of the Little Ice Age in 1850, there were about 80 glaciers in Glacier National Park. Still, other sources quote that there were 150 when the park was founded in 1910. Whichever way you count it, in 2015, only 26 named glaciers met the criteria of .1 km squared. Between 1996 and 2015, aerial surveys show that every named glacier in the park shrunk, some by more than 80%, because when it gets hot … ice melts. Grinnell Glacier is one of the park’s most famous examples of glacier melt. Currently, Grinnell Glacier spills into Upper Grinnell Lake, which is compromised entirely of ice melt and did not exist at the time of the park’s founding in 1910. Repeat photography is a great way to see the impact of rising temperatures on glaciers in the park.

If the glaciers are disappearing… why do you call it Glacier National Park?

North Cascades National Park actually has the highest concentration of glaciers in the lower 48. Even Glacier National Park’s website name-drops a slew of other places to visit before talking about their glaciers in a blog titled “How to See a Glacier.” With many of Glacier’s glaciers expected to disappear within this generation, a common question is, “Why is Glacier National Park called Glacier National Park, and will it still be called that when the glaciers disappear?” The truth is, Glacier is partially called Glacier because of the ice that used to exist here. In fact, the Kootenai name for the Glacier region is Ya·qawiswit̓xuki, which translates to “the place where there is a lot of ice.” But the exciting answer is that Glacier will always be called Glacier because when we talk about the park’s name, we’re referring to two things: the glaciers in the park and the unique glacial geology that Glacier is most famous for.

Some examples of that Glacial geology include:

Arêtes

Arêtes are thin and jagged ridgelines formed by two glaciers carving on either side of the ridge. A famous example of this in Glacier is the Garden Wall which you can see from Lake McDonald, the Going-to-the-sun Road, the Highline trail, or the other side of the wall on the Grinnell Glacier Trail.

Horns

Horns were formed when a mountain was scraped vertically by glaciers on three or more sides to create a thin horn-like shape. Some good examples are Little Matterhorn, which you can get a great view of from Snyder Lake, Mount Reynolds, which you can check out at Logan Pass, and Flinch Peak in Two Medicine.

Cirques & Tarns

A cirque is a bowl left behind where a glacier carved out rock in a scooping fashion. You can think of the glacier as an ice cream scooper and the cirque as the Ben and Jerry’s pint it’s putting a dent in. A tarn is the lake, ice, or debris filling a cirque.

Paternoster Lakes

Paternoster Lakes are trails of lakes left behind as a glacier retreated down a valley and scooped out several depressions. Interestingly, they are called this because they resemble rosary beads strung together. Swiftcurrent Valley is a perfect example, with Bullhead Lake, Redrock Lake, and Fishercap Lake forming their own “string” of paternoster lakes.

Moraines

Moraines are piles of rock and debris left behind by glaciers. A terminal moraine is a dump left at the end of a glacier’s trail. Lateral moraines are the debris pushed to the side as a glacier carves its path. Bonus-fun-fact-not-related-to-Glacier: Long Island in New York is the terminal moraine left behind by the glaciers that carved out the Hudson River Valley.

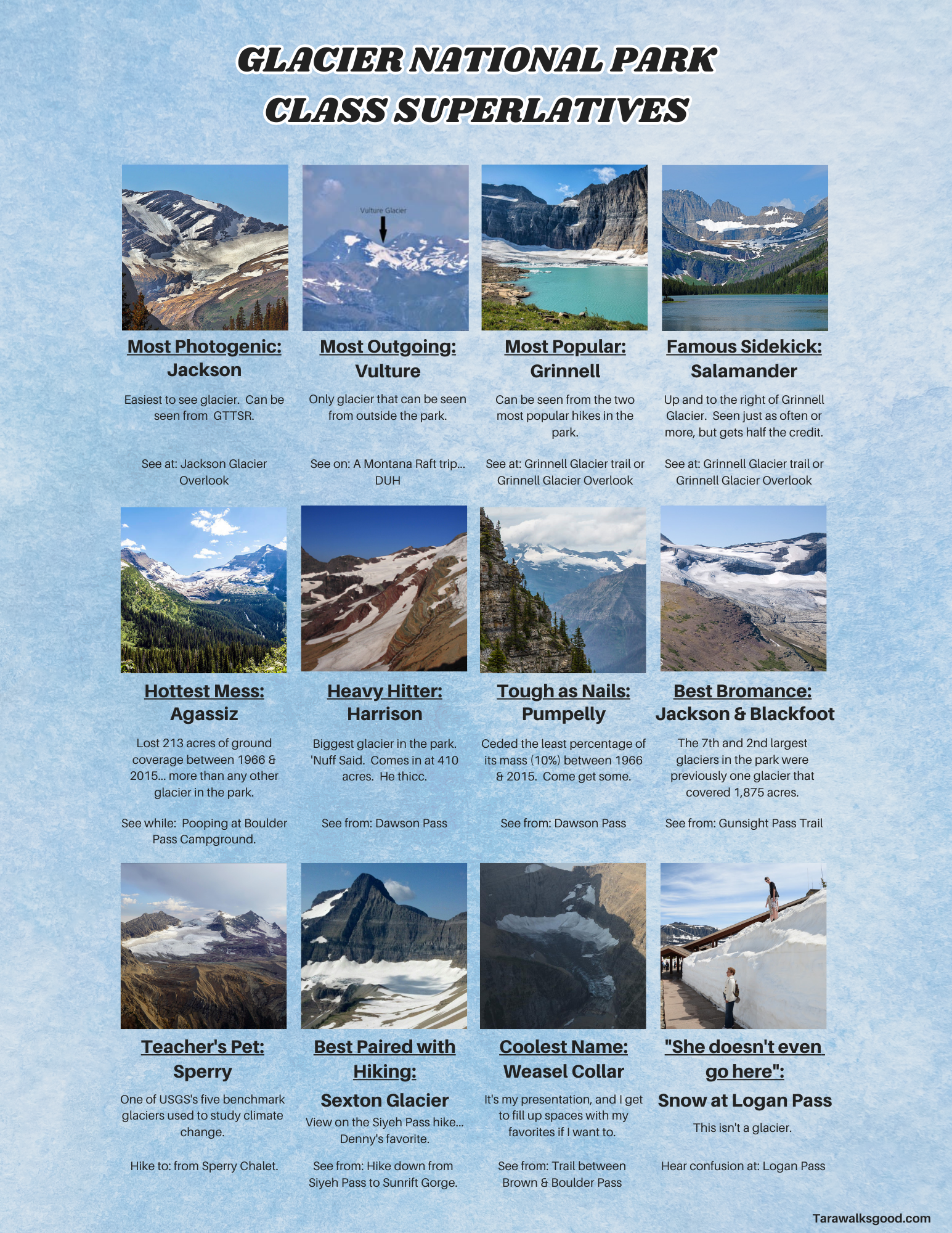

So that’s all well and cool, but let’s be honest: you want to know about the glaciers and where to see them. I get it. I’ve created a little cheat sheet for you here, reviewing some of the key named glaciers still left in the park, why they’re significant, and where you can see them. And I did them High School Class Superlative style because I thought it would be fun for me. And it was. Please enjoy!

Sources & Suggested Reading:

Overview of Glacier National Park’s Glaciers by Glacier National Park

How to See a Glacier by Glacier National Park

Mapping 50 years of Melting Ice in Glacier National Park by The New York Times